As noted in ISO 31000, Risk Analysis involves development of an understanding of the risks. Through risk analysis causes and effects of risks are identified, along with the likelihood of their occurrence. It also provides input into determining whether treatments are required.

Risk analysis is the process of characterising the risks that have been identified using the processes outlined in Risk Identification. It is typically broken into two distinct stages or aspects: Qualitative Risk Analysis and Quantitative Risk Analysis. These stages are sequential because quantitative risk analysis cannot be undertaken without qualitative risk analysis preceding it.

These two aspects of risk analysis are considered in turn.

Most of what ISO 31000 expresses about risk analysis is Qualitative Risk Analysis (QlRA).

QlRA involves considering the causes and consequences of risks and their likelihood of occurrence. The scale of each of the applicable types of consequences is considered, as is the level of likelihood. QlRA considers risks individually rather than the overall effect of the identified risks on the project.

ISO 31000 is careful to use qualitative terms for levels of risk likelihood and consequence and emphasises that the extent of uncertainty applicable to the determination of likelihood and consequence levels should be documented. It distinguishes between qualitative likelihood (expressed in levels) and quantitative probability (expressed in fractions of 1 or percentages). Likewise, it distinguishes between qualitative consequences (expressed in levels) and quantitative impacts (expressed in quantifiable units such as time or cost).

The UK Association for Project Management (APM), in its publication Project Risk Analysis and Management (PRAM) Guide (2nd Edition 2004), defines qualitative (risk) assessment as “an assessment of risk relating to the qualities and subjective elements of the risk – those that cannot be quantified accurately. Qualitative techniques include the definition of risk, the recording of risk details and relationships and the categorisation and prioritisation of risks relative to each other” (the last aspect referring to the risk evaluation step of risk assessment).

PMI does not distinguish between qualitative and quantitative terminology in its Practice Standard for Risk Management. It equates likelihood with probability and consequence with impact and defines the performance of Qualitative Risk Analysis as “The process of prioritising risks for further analysis or action by assessing and combining their probability of occurrence and impact.”

Our recommendation is to accept that QlRA is the subjective assignment of levels of likelihood and consequences (of various categories as applicable) to risk events and, where possible, to express the lower and upper thresholds of those levels semi-quantitatively, as probability percentages and impact values (cost, time relative to the total project budget and duration), during the initial step of the risk management process: Setting the Context.

In qualitative risk analysis, a Probability / Impact (PI) Matrix is usually used to represent the severity of a risk, using the assumption that risk severity or magnitude is the combination of likelihood and consequence. In semi-quantitative terms, Risk Exposure = Probability x Impact.

Risks are assessed for probability along the vertical axis, and impact is assessed along the horizontal axis. However, the impact units and thresholds are different for different category consequences. This is what enables risks of differing consequence categories to be combined in the one PI matrix and ranked in the one qualitative risk analysis register.

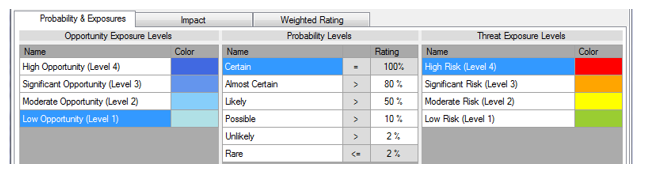

An example Probability and Exposure Level Guide to the PI Matrix that follows is shown below, for both Threats and Opportunities. The Exposure Level colour matches the level number in the scheme illustrated.

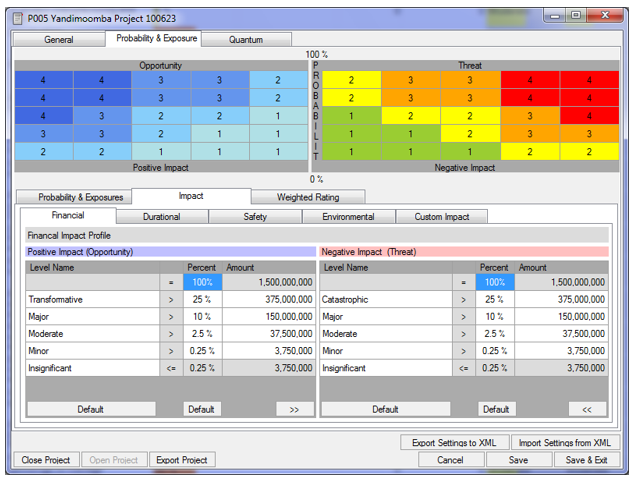

This approach is shown in the following PI Matrix for a Financial Impact matrix for a project with a value of $1.5 billion (100% impact). Each cell in the matrix is numbered according to the level of risk exposure. Organisations typically have different processes for handling risks according to the exposure level. Level 4 threats may be required to be referred to the Chief Executive or the Board Risk Committee, while level 3 threats may have to be dealt with by the Project Manager and level 2 threats and below may be managed by the project Risk Manager. Other numbering systems may be used, such as where each matrix cell has a unique number but the numbers within an exposure level are greater than the numbers in the level below and lower than the lowest number in the level above.

Semi-quantitative risk analysis extends this concept to apply numerical thresholds to the matrix cell edges. In the example above, a minor impact financial risk has been defined as being one with a value greater than $3.75 million but less than $37.5 million. These numbers define the vertical edges of the impact levels moving from left to right along the horizontal impact axis.

A similar process defines the horizontal edges of the five levels of the vertical probability axis. So for the Probability thresholds defined in the Probability and Exposure Level Guide above the PI matrix, the four boundary thresholds between Rare, Unlikely, Possible, Likely and Almost Certain are 2%, 10%, 50% and 80% respectively

The semi-quantitative matrix allows for finer delineation between risk exposures, as risks can be placed either low or high within each square. A qualitative matrix would place them at the mid-point of each cell.

Qualitative Risk Analysis is the entry step for risk analysis. It must be performed before quantitative risk analysis can be used. In addition it is the only way by which risks of all kinds of impact categories can be integrated into the one register. So risks describing Environmental, Health and Safety, Operational, Business and Reputational Impacts can all be included in a single Project Risk Register even though they do not have a commonly quantifiable metric for impact.

As noted above Qualitative Risk Assessment enables the comparative rating of environmental, reputational, health and safety, and other qualitative impacts that cannot readily be reduced to a single unifying metric such as a financial or durational impact. Taking safety risk as an example, a risk could be rated for impact on a scale ranging from “First Aid Injury” through to “Multiple Fatalities”.

Furthermore, where risks cover difficult or intractable problems for which no obvious treatments are apparent, qualitative risk analysis offers the best means of continued management and development of resolution.

However, qualitative approaches to risk analysis are unable to provide an overall measure of how risky a project is. For this Quantitative Risk Analysis is required. In addition, qualitative risk analyses start to show their limitations when a greater level of definition is required to inform decision making. Qualitative systems become cumbersome to work with when increasing the number of likelihood and consequence levels, and may still fall short of truly identifying the relative exposures of different risks in the register.

Additionally, qualitative systems are hampered by linguistic barriers associated with the individual’s interpretation of the qualitative terms. This is because the meaning inferred through usage of terms changes both between individuals and cultures. Some methodologies take a semi-quantitative approach to defining qualitative risk metrics to deal with this difficulty. This is achieved by defining quantitative thresholds associated with each qualitative label, as described above and distributing these at the start of the risk identification / rating process.

Quantitative Risk Analysis (QnRA) of a project models project uncertainty and risk events to produce numerical outputs expressing the riskiness of the project overall at differing probability levels. Quantitative risk analysis can reveal more about the potential impact of risks on a project than traditional qualitative risk registers that typically only rank risks via a “heat map”. One of the most used QnRA techniques is Monte Carlo modelling which can produce rankings of contributors to uncertainty (see 3 Schedule Risk Analysis using Primavera Risk Analysis (PRA)).

Quantitative risk should be used in any situation where a project is to be undertaken that is either too complex to assess by traditional qualitative means, or where the project is of significant importance to the organization undertaking it. QnRA can be used on any project involving quantifiable measures however and often provide a great deal more value to a project through examination and reporting of risk and uncertainty drivers and behaviours.

One of the primary distinctions between qualitative and quantitative assessments is that quantitative assessments can allow for evaluation of range uncertainties as well as distinct risk events. This means that a quantitative model can deal with estimating inaccuracies as well as events that may or may not occur. This results in a more comprehensive model of uncertainty on a project.

Unlike qualitative techniques, quantitative analysis also allows you to model the consequence of risks as they apply to a model of a project or scenario. This is important in schedule risk analysis as a schedule risk may have a high impact rating, but it may have no impact on the overall model completion if it applies to an area of the schedule with high float. Similarly, risks in quantitative models can be assessed concurrently. This means that if two risks fire together, it is possible to model that one risk supersedes the other and the impact of the second is nullified.

Quantitative risk assessment is sometimes criticised for its complexity. Quantitative risk assessments can be rendered of little use or worse, downright misleading by being facilitated by persons with little or no experience in performing them. Quantitative risk models are complex to get right and should be handled by consultants who work with them day in and day out and thus develop the necessary depth of knowledge to produce realistic and reliable results.

Wherever it is necessary to base risk analysis inputs on stakeholder opinions, it is crucial that a broad cross-section of project representatives be involved in order to obtain a balanced perspective of project uncertainty. Ideally, stakeholder involvement in determining project uncertainties should involve:

• Balanced representation of all parties where potential for conflict of interest exists - In some circumstances, multiple parties may be involved with conflicting vested interests in seeing a more optimistic or pessimistic result from a risk analysis. In such circumstances, it is important that representation is given to all parties involved so as to minimise bias.

• Representatives of all facets of project delivery – In most complex projects, responsibility for different facets of project delivery is delegated to a range of personnel according to their individual specialisations. In such circumstances, it is important that one or more representatives from each specialisation be included in the risk ranging and identification processes in order to gather the most accurate and informed cross-section of information possible.

• Both junior and senior project personnel – Junior personnel add value as they’re usually more actively involved in performing the work and may have a more “hands on” feel for current areas of potential uncertainty. Senior personnel bring a wealth of experience and are very useful for identifying areas of concern from past projects. Additionally, senior personnel are usually privy to additional information that may not be available to the more junior representatives that might be pertinent to the eventual risk outcome.

Ultimately, in order to obtain a truly accurate outcome from a risk analysis, the process should be as impartial as possible. This is difficult to achieve for most persons working directly within a project team because they’ll usually be answerable to a senior member of the project team with a vested interest in obtaining a result that fits with expectations in order to get the project “over the line”.

Specialist independent risk consultants are not bound by the same constraints and can often bring additional skills to the table that will likely result in a quicker and more accurate analysis than those conducted “in-house”. However, even when using independent consultants, it is desirable that they be engaged and be answerable to the organisation rather than the project team in order to remain truly independent.

According to ISO 31000, the process of risk evaluation involves assessing each risk against the objectives of the project and external criteria to see whether the risk and/or its magnitude (exposure) are acceptable or tolerable to the project. As stated earlier, a risk is only a risk insofar as it directly impacts on objectives. External criteria usually refer to compliance with safety, environmental or other statutory requirements or legislation. Risk evaluation assists in determining whether risk treatments are required in addition to existing controls, to bring the risk within an acceptable exposure for the project organisation.

Except where determined by safety, legislative or financial insurance requirements, there is typically no right answer as to what constitutes an acceptable risk. Evaluation of risks and the decision as to what constitutes an acceptable response plan ultimately depends on an organization’s “appetite” or “tolerance” for risk, the nature of the risk, and the organisation’s ability to influence factors contributing to or stemming from the risk. Also relevant is the risk management context of the project (how important the project is to the organisation and the resources available to manage the risk).

In the specialised field of technical and safety critical risk management, there are criteria for deciding acceptable levels of risk and by implication, treatments, expressed in the terms “As Low As Reasonably Practicable” (ALARP) and “So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable” (SFAIRP). These terms define the limits to which organisations with a Duty of Care (eg, Transport Authorities) are required to go to protect human life etc. The terms are used to distinguish the required efforts from whatever is possible, which may be grossly disproportionate to the increased level of protection resulting. This kind of Risk Management is outside the scope of this Knowledge Base. Further information on these areas may be obtained by inputting ALARP or SFAIRP into a search engine.

In many organizations, a decision authority matrix may be in place to formalise the sign-off procedures for the evaluation and subsequent management of risks. A decision authority matrix itemises the thresholds of risk consequence (probability * impact) at which risks must be reported and / or their treatment strategy approved.

After evaluating risks, the next step in the process is risk treatment. Risk treatment refers to risk action plans relating to the general strategies of elimination, allocation of ownership & modification of exposure. The first step in risk treatment is to assess what responses are most appropriate to deal with the risk.

Each of these strategies is discussed briefly below (more details are provided in Section

Risk elimination refers to the removal of uncertainty from a risk. The probability of occurrence is converted to either 0% (for threats) or 100% (for opportunities).

Allocation of risk ownership refers to the process of enacting contracting strategies or similar to modify exposure to a risk. This approach accepts that we will not be modifying the actual characteristics of the risk (probability or impact), but that it is possible to modify our exposure to it by sharing exposure with a third party. It is worth noting that it is rare to be able to transfer a threat entirely to another party, whether contractually or by insurance. It is usually more realistic to define the process as sharing.

For some risks, we may be able to modify the potential impact or probability of the risk occurring to mitigate or enhance its consequence. In the case of threats, an effective risk treatment would reduce the probability of the risk occurring or its impact should it occur. Conversely, in the case of an opportunity, effective risk treatments would increase the probability that the organisation could capitalise on the opportunity and/or its beneficial impacts should it occur.

To assess the efficacy of risk treatments, it is important to compare the risk exposure rating both pre and post treatment. This is often referred to as pre- and post-mitigation, even though several other treatment types are possible, as noted above.

The post-treatment risk rating is referred to as the “residual risk”. Maintaining an understanding of the pre-treatment risk assessment rating is important as it helps to understand what the exposure if risk treatment plans are not implemented or they fail to control the risk adequately.

This is a key part of Risk Management that is often under-emphasised. Effective implementation of risk treatments is crucial and may involve creation of mini-projects. Treatments may be pro-active, requiring deterministic expenditure of effort and money, or may be contingent, involving detailed planning for actions to follow immediately the occurrence of the risk is detected. Without implementation of effective treatments, Risk Management may achieve little.

Communication and Consultation is an integral part of the risk management process. It informs every stage of the risk management process and should involve both internal and external stakeholders. Because it is about future uncertain events, Risk is based on opinion which in turn is based on perception. Perception can be informed by values, needs, assumptions, concepts and concerns. All of the aforementioned factors will likely vary from stakeholder to stakeholder, so getting a balance of stakeholder perspectives is essential.

As identified in ISO 31000, a consultative approach to risk management may:

• Help establish the context appropriately;

• Ensure that the interests of stakeholders are understood and considered;

• Help ensure that risks are adequately identified;

• Bring different areas of expertise together for analysing risks;

• Ensure that different views are appropriately considered when defining risk criteria and in evaluating risks;

• Secure endorsement and support for a treatment plan; and

• Enhance appropriate change management during the risk management process.

Effective risk management is not a “tick-the-box” exercise. It is not something that can be done up front then parked in a corner somewhere. To truly add value to a project, risk management must be regularly monitored and reviewed to ensure that the risk monitoring and assessment are up to date and risk treatments are being implemented as agreed in a timely way.

Essentially, the risk management system must be proactive rather than reactive in dealing with risk. It is only by regularly re-examining the known and potential sources of risk and their potential consequences that informed decisions can be made to help reduce exposure to threats and capitalise on opportunities.

ISO 31000 identifies the benefits of effective monitoring and review processes as:

• Ensuring that controls (and treatments) are effective and efficient in both design and operation;

• Obtaining further information to improve risk assessment;

• Analysing and learning lessons from events (including near-misses), changes, trends, successes and failures;

• Detecting changes in the external and internal context, including changes to risk criteria and the risk itself which can require revision of risk treatments and priorities; and

• Identifying emerging risks.